Many years before founding Giant Leap Consulting, I was a member of the U.S. High Diving Team. Every day I would climb to the top of a hundred-foot high-dive ladder (the equivalent of a ten-story building) and stand atop a one-foot-by-one-foot perch. Then, after a quick prayer, I would leap into the air like an eagle taking flight. Except eagles soar upward. I never did. I would always go down, careening at speeds of over fifty miles per hour into a pool that was only ten feet deep. Fifteen hundred high-dives, all done with no parachute, no bungee, and no safety gear. High diving is considered one of the most dangerous sports in the world.

One dive stands out as having provided me with an important lesson in leadership role modeling. The team had been asked to perform during the annual Osmond Family Fourth of July extravaganza at Brigham Young Stadium in Provo, Utah. We were part of a lineup that included Donny and Marie, the rest of the Osmond family, singer Crystal Gayle, and actor Mr. T.

More than fifty thousand spectators were expected to attend the show. In addition to our performing a sensational repertoire of Olympic-style dives, the entire extravaganza was to culminate in a huge fireworks display as a high diver plunged from the top of the ladder while holding two lit flares, one in each hand. The dive was to be performed to “The Flight of the Bumble Bee,” the frenetic musical piece from the opera Tsar Sultan.

But there was a little problem. Unbeknownst to the Osmond family, none of us “big shot” divers wanted to do the spectacular crescendo dive. First of all, the dive would be done in the glare of a blinding spotlight after all the other stadium lights were shut off. Second, diving with two lit flares would severely limit the diver’s arm movement, something that is critical for performing aerial acrobatics. Finally, having to dive among all the exploding pyrotechnics presented dangers beyond reason. The thought of getting blown up by an errant sky bomb was less than inviting.

After growing annoyed with everyone’s bellyaching, our most seasoned veteran, Hamilton Riddle, volunteered to do it. To appreciate the magnitude of this gesture, you have to know Hamilton. At six-foot-five inches and 240 pounds, Hamilton is a Goliath of a man. Because the diving tank was only ten feet deep, Hamilton wouldn’t have much stopping room. And though he was incredibly fit, “H” (as we called him), at forty-five years old, was the oldest eagle in our flock.

Through the rose-colored glasses of hindsight, it is tempting to view Hamilton’s volunteering to do the dive as having something to do with his having larger cojones than the rest of us. The more accurate truth is that he had more to lose in not doing the dive. Hamilton was a part owner of the production company that was responsible for staging the high-diving show, and a lot of his own money was at stake. The Osmond’s had forked over a healthy sum for the show, and now it was up to us to deliver. Since everyone else had backed down, what choice did Hamilton have but to step up?

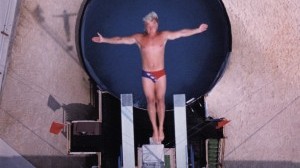

The dramatic moment when the spotlight illuminated Hamilton atop the ladder will always stay with me. There he was, this colossus of a man, arms outstretched to the sides like some mythic aerial savior, fireworks exploding all around him, perched at the top of the world. For a brief moment, Hamilton wasn’t Hamilton. He had morphed into high-diving’s senior-most archangel. His spectacular flare dive was glorious and humbling to behold. The crowd erupted with a huge applause as he surfaced the water, fists raised in triumph. At once he represented all that each diver could have been and all that we had declined to be.

Desperate or not, Hamilton had stepped up when we had backed down. He had role modeled what it means to be a leader by Leaping First.